Drumadoon Fieldschool, Arran, August 2025

Published: 7 October 2025

Update Part I

One of the delights of fieldwork is experiencing different environments and considering how these have changed through time. This summer, our fieldwork took us onto the upland bog above Drumadoon.

At first glance, the landscape may appear untouched by people, although faint earthworks concealed within the heather gave echoes of the prehistoric houses and cairns as we made the climb up onto the bog. Subtle differences in the colour of the vegetation revealed that the heather is made up of different species; dominated by ling (Calluna vulgaris), with pockets of bell heather (Erica cinerea). Upon closer inspection, the heather is full of life, from grasshoppers to spiders, such as the 4-spotted orb weaver Araneus quadratus.

The ground became wetter and softer as we ascended, and the subtle rectangular shapes of historic peat cuttings came into view, made all the more clear by different vegetation communities occupying these wetter hollows. Making sense of the complexity of human activity within this remote environment requires an appreciation of both the ancient archives preserved within the metres of peat below our feet and the subtleties of the existing vegetation.

Nearing our coring site upon the quaking surface of the bog, we saw the distinctive plant communities that are only seen within these acidic and nutrient poor environments. The glistening red sundews (Drosera spp.), the trifoliate leaves of bog bean (Menyanthes trifoliata), and the reds and greens of the Sphagnum mosses.

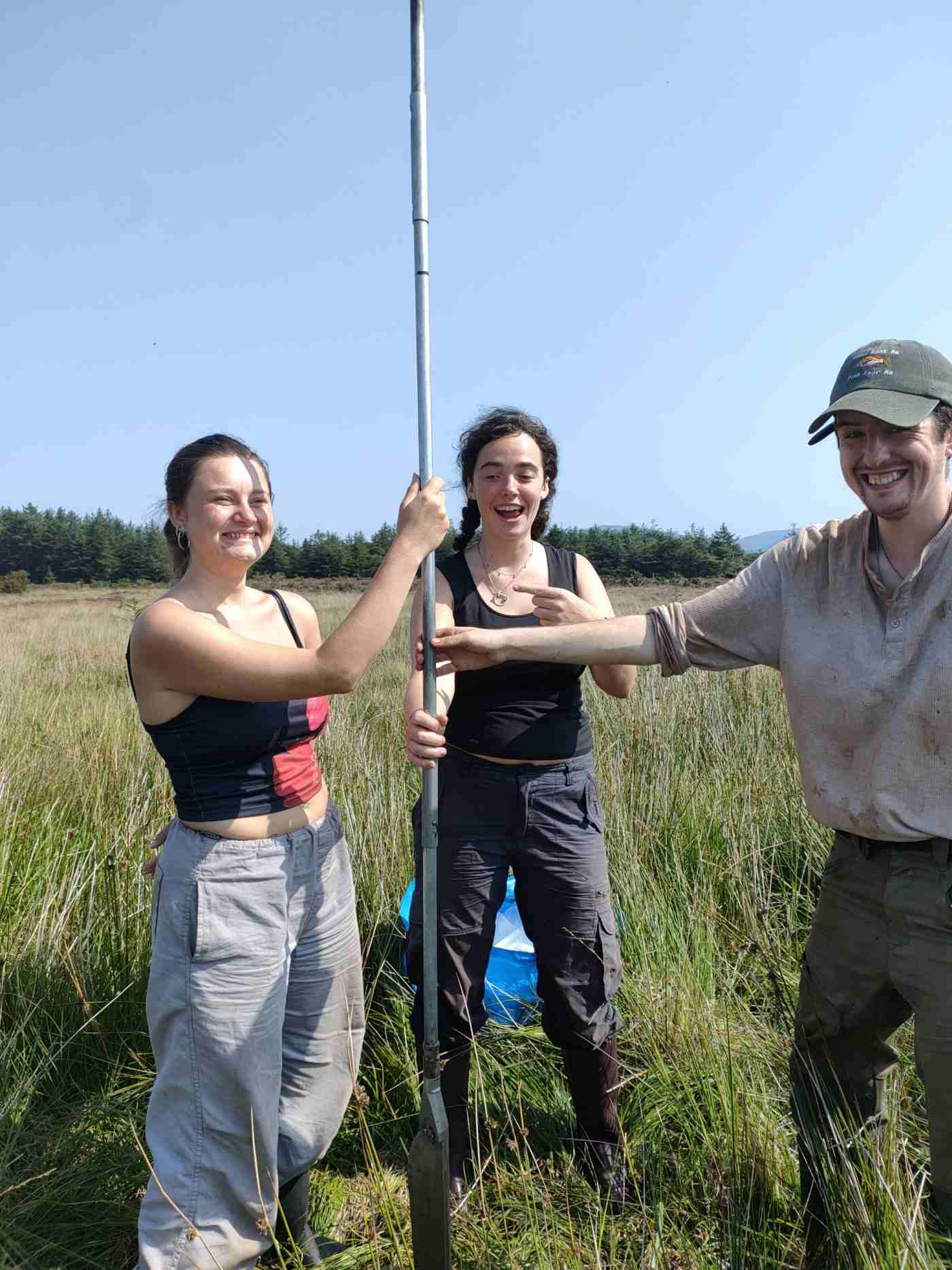

The health of the peatland above Drumadoon became clear through the boreholes taken, and provided a clear reason for the instability of the surface. For over a half a metre below us, deposits were so saturated that it was a challenge to recover sufficient material for lab analysis. By the end of our time on the high bog, we had recovered two sequences that would be brought back to the lab for analysis to provide new evidence relating to the long-term landscape history of this landscape.

This important work is allowing us to understand how this incredible landscape evolved and changed over time and in turn how people made use of and transformed this place. The Drumadoon bog is full of prehistoric archaeology from the Neolithic and Bronze Age, including a Neolithic cursus monument, an extensive system of field boundary walls, prehistoric hut circles, and cairns and more recent drove-ways, tracks and peat cuttings. It’s a fascinating place both for archaeology and nature.

We hope to return next year.

Henry Chapman, Michelle Farrell and Nicki Whitehouse

You can find out more about the Drumadoon project here.

First published: 7 October 2025

<< Latest news